Suzanne Jabbour’s fight against Torture: “My battle horse is humanity”

Suzanne Jabbour, 58, is behind numerous projects aimed at protecting Human Rights. The most recent is a small revolution in the region: setting up a joint medical-legal centre at the Courthouse in Tripoli. The project is funded by the European Union’s “Joint Action for an Effective Prosecution of Torture and enhanced commitment to the Prevention of inherent crimes,” to the tune of €1,283,000. Discover Suzanne Jabbour’s story, and how and why she has dedicated her whole life to defending social justice.

“One night in spring 1975 during the civil war, my mother woke us up because the bombings were escalating in our village of Ardeh in the North of Lebanon. I was 13 years old. We had to leave in a panic, sick with fear and unable to take anything with us, in order to flee temporarily to my grandmother’s house nearby. Even there, we had to lock the doors and barricade ourselves in as we could hear the military surround us. It was terrifying. I am the youngest of seven children and that night there were just fifteen women, a three-month old baby and my brother who was wounded. The men in my family needed to guard their businesses in the Zghorta region.

That night changed everything. It was the first time that I felt hatred: against the military firstly. And against war in general. It was a new feeling for an adolescent like me. I asked myself a whole host of questions: why us? Why do we have to live like this? What could these people possibly want? Why the war? What about humanity?

It all triggered a need in me to voice my opinion on these questions. That is how, at age 13, I began writing, inspired by my father who was a poet in his spare time.

I began to dream of becoming a journalist. When I was 17 a few of my articles were even published in newspapers. I had so many things to talk about. My battle horse was humanity. I wanted to cry that we needed to think of our future, that this brutality didn’t make any sense and was hurting us all. The title of one of the articles I had in mind was: “Let our people live, they want to live!”

But I could never have become a journalist. After finishing college, I wanted to study media at the Lebanese University, but I was rejected. They only wanted journalists who defended their beliefs and that wasn’t me. That is how I ended up enrolling in psychology at the Lebanese University, somewhat randomly.

But I could accomplish my dream of defending human dignity against all odds. Everything that I have accomplished in my life I have been able to achieve thanks to this psychology training.

“I noticed that there was no structures to help children with learning difficulties”.

Once I was qualified, I wanted to put my psychology degree into practice. But at the time mental health was a taboo subject. The mentality was that if you consulted a psychologist you were “crazy”.

I only had a few options including being a specialised teacher or a careers adviser, but I never wanted that; I always felt I was capable of more. When I was 17 years old my father had an ulcer. It fell on me to take over his work. I studied and looked after his business affairs at the same time. It was under these circumstances that I achieved a lot of personal growth and self-confidence. I proved to myself that I could be a good manager.

Then in 1988, when my university classmate Sana Hamzé suggested setting up a psychology project with her, I leapt at the chance. We carried out a survey on the needs in the region of Tripoli. We discovered that there was nothing to help children suffering from learning difficulties. That is how we had the idea of starting a specialist psychology clinic to help them.

Once the clinic opened, we welcomed lots of children who suffered from disabilities, particularly deaf children. And that is how we created our NGO specialising in helping deaf children in 1989, Friends in Need.

At the clinic we continued to welcome children suffering from other disabilities, not so much physical, but intellectual, such as Downs Syndrome. These children needed somewhere to learn at their own pace and in their own way. We had the idea of creating a trial pilot classroom in the clinic to welcome some of them and offer them an education adapted to their needs.

When my sister had Chady, a child with an intellectual disability, we were even more motivated.

We invested heavily in the project and I even sold my car so I could buy a larger vehicle and hire a driver to pick up children with disabilities from their homes. Most families were in need but did not have the means to bring their children to the clinic every day.

We began with six children including Chady. Two years on, we had more and more children, and the needs were ever growing. We merged our activities with that of one of our colleagues in Beirut who worked on the same issues. That is how the NGO Fista was founded in 1991, a free school for children suffering from mental disabilities and learning difficulties. We now receive 250 children per year, with three branches in Tripoli, one in Akkar and one in Beirut. We are just about to open a 4500m2 site near Tripoli in September to welcome even more. We have helped 7000 children since 1989.

“We have identified many victims of torture”

It was through working on Fista that we had the idea for our next project, Restart. When children arrive at Fista, our social worker fills in a questionnaire on their background to find out more about their circumstances, such as: where they are from, what their family do, etc. We discovered that some of the parents of the children we looked after had been victims of torture and were still suffering trauma.

We wanted to help them, but we didn’t know how. That was until Sana met Inge Genefke, founder of the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims (IRCT) during a visit to Copenhagen. She suggested creating a specialised centre to help victims of torture in Lebanon. And so, Restart was founded in 1996. Through Restart we’re fighting to prevent torture and helping victims recover and reintegrate into society. Our centre is based in Tripoli and since opening we have worked with former prisoners from the whole region. Ten years later, we opened a branch in Beirut in order to further extend our reach.

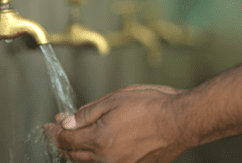

As the victims of torture we welcomed were mainly former prisoners, we wanted to work directly with prisons, where there was a greater need. In 2004 we started working in the Kobbe prison near to Tripoli. The building is very old, dating back to the French mandate and is overcrowded; so much so that the prison conditions are very harsh and the mistreatment there could equate to torture.

Based on the principle that all people, no matter what they have done, have the right to have their dignity respected, we proposed that the government provide free medical care, activities and help to prisoners. That is how Restart began working in prisons in 2005. Since 2007 the European Union has helped us every year by funding at least one project which aims to improve the living conditions in prisons.

Thanks to them, at Kobbe prison we have been able to build a medical centre, a psychology cell, a library, dental clinic and a bridge joining the prison to the medical centre.

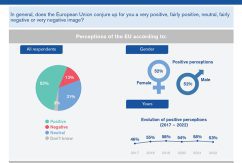

“One of the European Union’s priorities is protecting Human Rights. It is for this reason that we are involved in the fight against mistreatment and torture in Lebanon with Restart”, explains the spokesperson of the European Union in Lebanon.

“In 2017 and since the beginning of Restart, we have helped all in all 17000 victims of torture, adds Suzanne Jabbour.

“Human Rights at any cost”.

In 2000 Lebanon ratified the United Nations Convention Against Torture (UNCAT), but it still has some way to go. Through our work, the Committee Against Torture and human rights organisations have shared their concerns with us on the use of torture in Lebanon. Having said that, Interior Security Forces are still a vital partner in our fight and have agreed to cooperate despite internal challenges.

In 2015 we had the idea of creating a joint medical-legal rehabilitation centre within the Tripoli Courthouse to prevent torture. The centre is managed by Restart and funded by the European Union to the tune of €1,283,000.

Every day our social worker distributes new booklets explaining the decrees, their rights and how the joint medical-legal centre works. Also, those who want to can be examined by the medical examiner, psychologist and lawyer before being questioned by police. A similar examination is then carried out after detention at the Courthouse.

To be accepted onto the project, it is essential that we work with the Ministry of Justice. The centre opened in 2017, but we didn’t start work until towards the end of 2018.

It is a sensitive subject that required a lot of negotiation with the different actors involved in order to change internal procedures. There is still a lot to be done to change the culture and mentality. Fortunately, with support from the European Union we can get there.”

“This project fits into the European Union’s more global policy of protecting human dignity on all fronts, whether in prison, in society or through the justice, legal and security system”, explains the EU’s spokesperson.

“Since starting”, Suzanne Jabbour continues, “we have interviewed more than one hundred prisoners and discovered many cases of torture. Tragically, none of the victims have pressed charges for fear of retaliation. Our aim is to have at least one prison guard prosecuted to serve as an example and dissuade others from continuing to carry out acts of torture.

This is my current priority; I want to put end the culture of impunity for perpetrators of torture. I want people’s attitudes to change and for them to understand that torture is not justified under any circumstances. When someone is arrested, they are deprived of their freedom, but not their human rights. “

EU Delegation